In enterprise infra, there’s no security without consistency

Meet the vulnerable app, in the vulnerable environment

Back in 2024, I was working for a cybersecurity vendor, living on the conference circuit performing live demos and talks all about Kubernetes security.

One talk in particular sticks in my mind. The goal was simple: show how a misconfigured workload can escalate into something much larger.

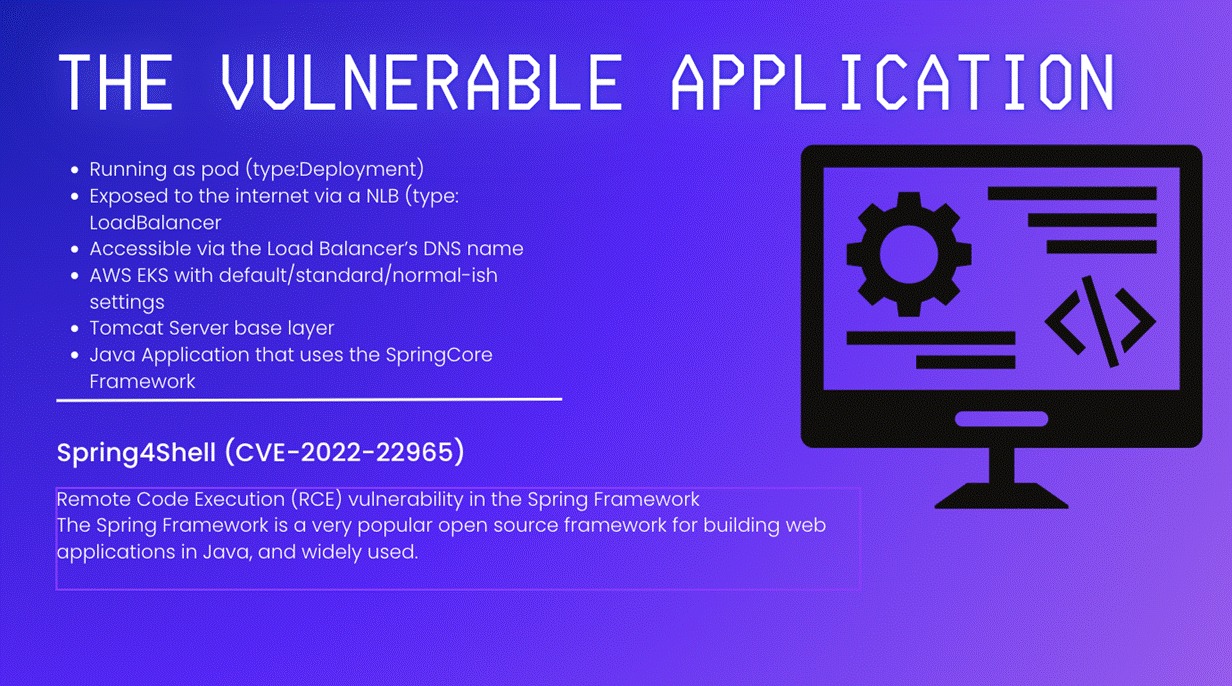

The container I deployed looked like something you would find in a typical engineering environment. (There’s probably one just like it in your environment, too).

It had elevated privileges because a team “needed it to work.”

The base image had not been rebuilt for some time and still contained a critical vulnerability published in 2022 (CVE-2022-22965).

The node also had access to the cloud instance metadata endpoint.

Like any exploit, it happens step by (easy) step

Once the container started, the sequence was predictable.

Get a shell. Use the extra privileges to reach the host filesystem. Query the metadata service. Retrieve information that should never be reachable from inside a pod. Oops.

As I was talking, I could see the audience was focused on the exploit. But I was more focused on the conditions that allowed it to happen.

In reality, none of them was unusual! They were each the result of normal engineering decisions made under pressure:

- A quick exception

- An image rebuild is delayed until later

- Defaults left untouched

This was the first lesson from the demo. Attackers often rely on common misconfigurations rather than advanced techniques (why work hard when you can walk in the proverbial front door?).

The second lesson came later. Several scanners could have easily flagged the vulnerable image and the configuration issues, enabling the developers and operations teams to fix the issues before the exploit happened.

In other words: the problem was not tool availability. It was uneven deployment across environments and clusters. Some clusters had the right scanners. Others did not. Some teams enforced privilege restrictions. Others did not.

The gaps were operational, not theoretical.

The cause? Configuration drift

If there was one common theme I saw during my years at the world’s largest cybersecurity company, it was how environments are often surprisingly inconsistent.

After joining Spectro Cloud, the connection between security vulnerabilities and environment inconsistency became clearer.

Most Kubernetes risk does not originate at runtime. It originates in how clusters are created and how they drift over time.

Most organizations understand the basics of Kubernetes hardening:

- Run workloads with minimal privileges.

- Keep images and base components current.

- Apply secure defaults.

- Scan images and configurations regularly.

In practice, the challenge is delivering on those basics with absolute consistency.

Kubernetes is inherently flexible (that’s one of the reasons we all love it, right?). Teams can choose different CNIs, logging stacks, ingress controllers, and security tools.

This flexibility is useful in development but creates drift when you see it working at scale.

One environment gets regular updates, while another stays pinned because teams are hesitant to change what is working for them and their apps.

A scanner runs on one cluster, but is missing from another.

Over time, clusters become similar in name but different in detail, and this impacts both risk and operational load.

In drifted environments, especially at scale, security teams are unable to answer simple questions such as “where is this tool deployed?” or “how many clusters use an outdated image?” Platform teams spend more time maintaining exceptions than improving the shared platform. Documentation trails reality, people leave, and dependencies become unknown.

The sad truth is that all these issues are extremely common in Kubernetes environments. They are the natural result of running many clusters without a structured lifecycle model. The exploit from my demo simply illustrated how these operational differences can align into a clear attack path.

So how do you enforce consistency?

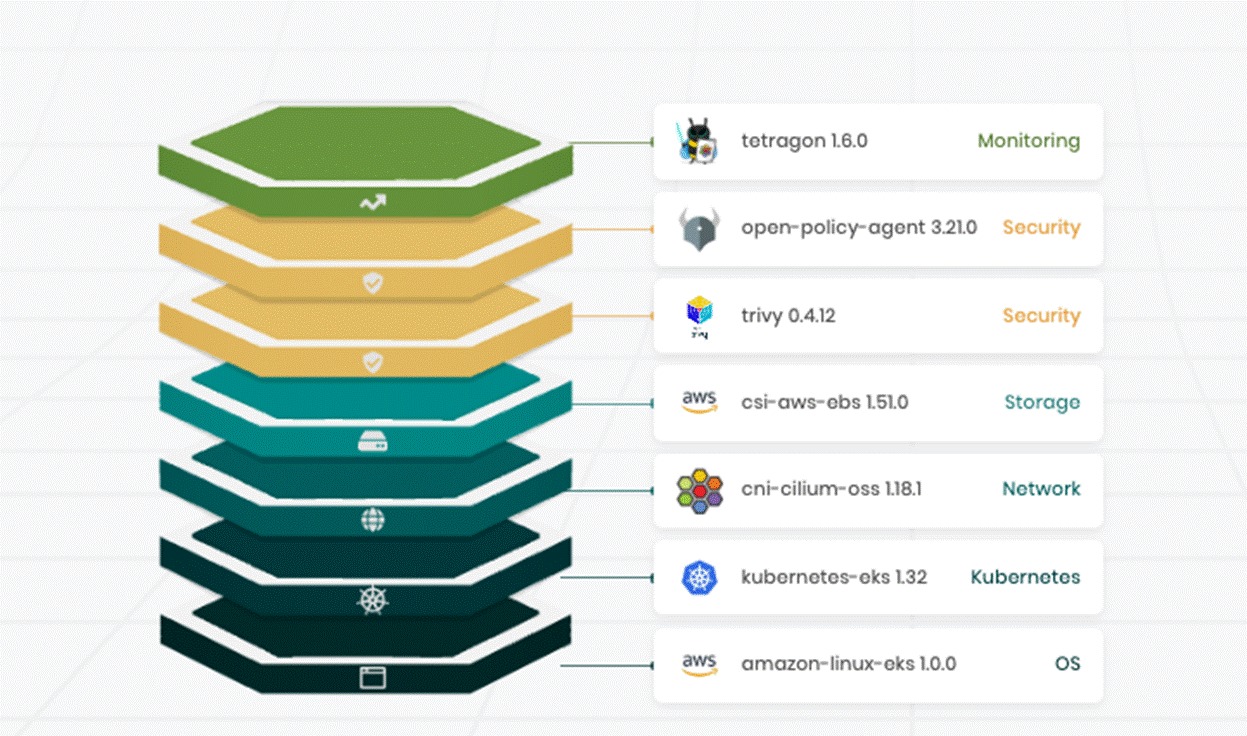

Palette tackles this problem by treating cluster definition as a declarative asset.

Cluster Profiles capture the full stack: operating system, Kubernetes version, networking, storage, and the add-ons that provide logging, policy, scanning, or runtime visibility. Instead of assembling these components differently for each internal team, platform engineers define them once and apply them wherever clusters are needed.

This reduces many sources of drift.

For starters, if policy engines, scanners, or runtime sensors needed for security are defined in the profile, they become part of the default build. Every cluster created from that profile receives them. Updates can be tested and rolled out centrally through versioned changes. There is no need to retrofit individual clusters after the fact.

Packs extend this by providing curated combinations of open-source components with known compatibility. You can use Spectro Cloud’s Palette Packs or build your own. The point is to make dependencies explicit and repeatable.

In the screenshot above, the example profile includes a policy layer, a scanning layer, and a runtime analysis layer. The specific tools shown are placeholders. You can substitute whatever you use today. What matters is that these layers become part of the cluster definition rather than ad-hoc steps that depend on individual teams (who are human, and might miss something).

The result is Palette gives platform engineers a practical way to deliver clusters that meet internal customer needs without accumulating a growing set of one-off configurations. You still maintain flexibility, but the foundation is clear and consistent.

A breach that could easily have been avoided

When I look back at the demo through the lens of drift and inconsistency, the compromise becomes easier to explain:

- A privileged pod that did not need to be privileged.

- An image that had not been rebuilt, even though a critical CVE had been public for two years.

- Access to instance metadata that nobody had reviewed.

None of these issues required a sophisticated attacker. They were configuration choices. They were also choices that could have been addressed earlier in the lifecycle if the cluster had been created from a profile with the right guardrails.

A declarative lifecycle model does not guarantee perfect security. It will not stop all misconfigurations. It does, however, reduce the number of places where risky patterns can appear and persist across clusters. Secure defaults become more common. Drift becomes less common. Known issues become easier to address at scale.

An ounce of prevention…

The main trade-off is the effort required to define and maintain the profiles that express these baselines. The benefit is a more predictable fleet and clearer coordination between platform and security teams. Platform teams control the shared foundation. Security teams can rely on the consistent placement of their tools.

Kubernetes will always have complexity and flexibility. That does not have to translate into unpredictable environments. A profile-driven, declarative approach gives platform teams a realistic way to improve both security posture and operational consistency.

That was the real lesson of the live hack. Most attacks begin long before runtime. They begin with the day-to-day decisions that shape each cluster. With the right structure around those decisions, the path to compromise becomes harder by default.

Want to learn more about Kubernetes security best practices, Cluster Profiles, and the security features built into Palette? You can book a demo right here, and read this blog to learn how we bake security into everything we do.

.avif)